Chapters 1 – 2

Chapter 1 –An Interrupted Dinner

Roger June’s finger stopped moving down the items on the wine list. His finger stopped on the lines Chateau Latour 1989 and Chateau Latour 1990. He knew he had drunk one or the other of these two superb vintages, but couldn’t remember which one. His eyes glazed over trying to mine this memory, and with his finger on the page, for a few moments he looked like a six year old trying to read.

When the memory attempt failed and his eyes refocused on the here and now, he didn’t like what he saw. He really, really didn’t like it, because what he saw was Little Jinny Blistov entering through the door of the restaurant. June and his wife were seated at a banquette table against the back wall, quite a distance from the door. June’s memory had failed him, but his eyes didn’t; he saw Blistov long before Blistov saw him. His right hand brushed aside the panel of his suit coat and he pulled his gun. The sound of him racking the slide under the table alerted his wife to an urgent situation. Being married to Roger for so many years, she was used to all sorts of urgent situations, life-threatening or not. She liked the not-life-threatening ones better, and of these, she liked the sexual ones best. Roger always made those lots of fun.

The sound of a slide racking on a semi-automatic handgun was common to Gwen. She had done this hundreds of times at the gun range, and a few times not on the gun range. However, the sound coming from under the table at one of Charleston’s fanciest restaurants did give her pause. But this pause was brief. Five seconds after hearing the sound, Gwen bent slightly, picked her purse up from the floor, and pulled out her own gun. Another ominous racking sound came from under the table.

Only when Gwen had her gun securely in her hand and her hand in her lap did she look out at the room. She didn’t need to look at Roger. His sound had told her everything, and she knew he had his gun securely in his hand and his hand in his lap. At least she hoped he had the good sense to keep the gun hidden and not just lay it on top of the table next to the wine menu.

Gwen scanned the thirty or so people in the room, and her gaze came to rest on the face of Little Jinny Blistov. She’d never seen Blistov before, but she knew his story. Her husband and Blistov had come face to face in the past, in a confrontational way. She didn’t know the guy standing out near the checkin desk was Blistov, but sure as shit she knew he was the guy who had garnered her husband’s very serious attention. She knew he was serious because he was not in the habit of pulling his gun while trying to select the wine to accompany their dinner. In point of fact, she couldn’t remember it ever happening before. She had been present a couple of times when Roger had pulled his gun in a serious way, but never before at dinner. This was a new one.

Gwen knew Blistov was the guy because he just didn’t fit into this restaurant’s crowd. The guy standing out there was not very Charlestonian in nature or presentation. Blistov stood five foot five, and weighed in at an even 200 pounds, yet he wasn’t fat. He had shaved that morning but looked like he last had shaved three days ago, and his whiskers wrapped backwards around the sides of his neck below his ears. He was wearing a black cotton sweatshirt and black cotton jeans, and on his feet were the ugliest pair of white sneakers Gwen had ever seen.

Gwen was thankful she was female because she was a shoe aficionado. She knew beautiful women should wear beautiful shoes on their beautifully sexy feet, and she performed this duty flawlessly. She was sorry for males, knowing they didn’t have beautiful feet upon which to wearing correspondingly attractive shoes.

Blistov’s shoes were so ugly she was tempted to shoot him on that count alone, never mind whatever was bothering her husband. There were plenty of people in the restaurant wearing black clothes, but they certainly weren’t made out of cotton. The dresses were silk, the suits were merino wool or better, and the mock turtlenecks were silk. A half dozen men were wearing silk socks. Blistov’s black stood out from all the rest of the black in the room, and Gwen didn’t like it.

She found the rather tight smile on Roger’s face mildly amusing. Gwen preferred her dinners to be uninterrupted by gunfire, but there was something oddly humorous about this situation. Here they are, essentially at ease within a world of ease, about to pull the string on ordering a $400 bottle of Bordeaux, and they find themselves face to face with an ex-Russian mobster who has a beef with Roger. Roger seems to think, as evidenced by the racking of the slide on his gun, that the beef might be serious. If Blistov’s issue was with Gwen rather than Roger, she might not find the situation so amusing, but as it was, well, she just smiled a bit inside.

This tells you something about Gwen. It’s nice when a wife has complete confidence in her husband to protect her. It’s really interesting when she has complete confidence in herself to protect her husband. Either way, Gwen knew with absolute certainty that if Blistov started anything, he was dead meat. With this thought her amusement disintegrated, she tightened the curve of her mouth, and went back to meditating on the hate she felt about his shoes.

Despite the look on his face that only his wife could tell meant he was in a serious mood, Roger was reasonably relaxed. The way a person grips their gun under stress tells you something about them. Roger’s grip was firm but relaxed.

By now Blistov had finished his scan of the dining room, and had located Roger and Gwen in their banquette table. He smiled and sent his 200-pound body into motion towards them. He not only acted like he owned the place, he acted like he and Roger and Gwen were the only people in the joint. He walked straight up to their table, stopped, looked at Roger, looked at Gwen, and said, “You heeled, Roger?” This amazed Roger, who knew what it meant to be heeled. Roger was shocked that a guy from Russia, and a criminal no less, knew an archaic and very American word like heeled. Roger liked to be surprised when it came to cultural trivia, so his estimation of Blistov was raised a tiny notch. To be heeled means to be armed with a gun. It is a cowboy word from the 19th century American west, and Roger had learned it reading Elmore Leonard’s old novels. Today, Leonard is known for writing crime novels, but he started his craft by writing westerns.

While Roger sat for a moment in amazement, with his appraisal of Blistov edging upward, the appraisal by his wife declined. In fact, right after Blistov asked Roger if he was heeled, Gwen let out an audible snicker. Inherent in the word snicker is an inference of derision, and that is exactly what Gwen felt. The reasons? First because Blistov asked Roger if he was armed, and second because of Blistov’s height. He is short. In Gwen’s eyes, he wasn’t just short, he was munchkin short. She thought Blistov could just walk up to a table and start eating, without even sitting down. Other people would sit and eat while Blistov would stand and eat, and essentially they would be equal. This vision is what made Gwen snicker. Not many women can snicker at someone while holding a gun, but Gwen can.H Hehh

While his wife was snickering, Roger said, “This is one of Charleston’s nicest and most expensive restaurants. People don’t bring guns in here.”

Blistov might be short, but he also was quite bright, and knew Roger was lying. He didn’t really care. He said, “Who’s she?”

Gwen hated this guy on two counts already: his shoes, and his adversarial relationship with the man she loved. Now she had a third count, the denegrating manner in which he had referred to her. Roger knew his wife thought and acted judiciously (most of the time), and he was pretty sure she wouldn’t shoot Blistov on just the first two counts, but when Blistov added count number three, Roger became a little apprehensive. He didn’t actually look at his wife, but he sent extra feelers her way to sense her mood.

In the great State of South Carolina it is a felony to point a gun at another person if that person is not threatening your life. Gwen knew this, so she resisted the temptation to stand up, stick her piece in Blistov’s face and say, “I’m Gwen, who are you, you little munchkin fuck?” What she did was elevate her snicker to an actual smile, stand up while hiding her gun behind her back, look Blistov in the eye, and say, “Roger, is this little munchkin fuck the Russian who stole your auntie’s money?”eHe

Chapter 2 – The Source of the Conflict

Blistov was Russian and had grown up in Saint Petersburg during the heyday of the good ole USSR. Jinny’s first job was cleaning toilets in the Hermitage Museum. Have you any idea how many toilets are in that place? It has something like 1285 rooms, and one heck of a lot of them are bathrooms. While Jinny was cleaning all day, he also was learning about the history of the palace, and thereby was learning the history of his country. Even though his days were spent looking at shitholes, his mind was developing an appreciation for gold-leaf gild, oil paintings of tables laden with caviar, boudoirs with commodes, and really big kitchens. There were kitchens in that place bigger than most of the houses in the city.

Jinny spent five years working at the Hermitage before he was introduced to crime by one of the security staff he hung out with. The lessons of those five years have stuck with him ever since, and explain why Jinny ended up crossways with Roger in Charleston. We never lose the lessons of our youth, good and bad. Jinny learned about fancy things then, and ever since he has wanted those things and worked diligently to procure them. He worked at a life of crime, first in Russia, and then in the United States. Basically, crime is the same no matter what country you work in. You find a crack in a facet of society, and you wedge yourself into it. Some wedging requires stealth, and some wedging requires brains, and some wedging requires violence. Jinny was capable of all those, as the need might arise.

Blistov was successful at crime over a period of about twenty Russian winters. Then, he wasn’t. He got caught messing with the money of a very powerful man, and the man decided it would be worse for Blistov to spend time in a Russian prison, and then suffer exportation, than just killing him. So he arranged for Blistov to spend three years away from the good life he had made for himself. Then, an hour after being released from prison, Blistov unceremoniously was driven to a military airport and stuck in the unheated belly of an Aeroflot cargo plane, without a coat, without a nickel, and without a Russian passport, bound for Pittsburgh, PA….the Iron City. Eleven cold hours later Blistov arrived, and he began his new life.

Blistov hated Russian winters. Physically he was a tough guy, but he hated the cold. So when he discovered Pittsburgh was plagued by cold winters, he said fuck this. It was bad enough to spend three years freezing in a Russian prison, and eleven hours freezing in the hold of a cargo plane, but he was damned if he was going to spend the rest of his life freezing in a cultural backwater like Pittsburgh.

Another thing Blistov had learned at the Hermitage was the historic link between King Charles the IV of France and Czar Brettany Prentikof. These two kings had developed a real fondness for each other based on a mutual love of hunting dogs. Brettany had sent a few Borzois to Paris, and in return Charles had sent a veritable kennel of Normandy spaniels to St. Petes. Charles was a Huguenot, and his heirs crossed the Atlantic way back when, landing in a very weird place called South Carolina. Lots and lots of Huguenots arrived and settled in Charleston. And being that Blistov always would tend to a life of crime, he came into conflict with Roger, and by proxy, with Gwen.

Roger met him about a year after Blistov arrived in Charleston. Jinny had moved to Charleston based on the following logic. A French king named Charles had given a bunch of mutts to his friend the Czar, who Blistov knew about from having cleaned toilets in the Hermitage that this czar had used three hundred years ago. Charles was a Huguenot, whose ancestors had immigrated to South Carolina (CharlesTown). Charles and the Russian czar were buds; ergo CharlesTown with its Huguenot population was a good place to live. So when Blistov said fuck this to spending another winter in Pittsburgh, to Charleston he came.

Blistov was a successful crook in Russia, where the boys have a tendency to play rough. He also was a successful crook in Pittsburgh, where he considered the other crooks to be a bunch of pansies. Even though he only lived in Pittsburgh two years, he had made some money, and he arrived in Charleston flush. This gave him time to relax and get to know King Charles’ town, now his town. He didn’t have to get down to crime immediately. To his delight, he discovered that even though Charleston is in South Carolina, it’s a place of culture. After renting a modest 4000 square foot cottage on the beach of Sullivan’s Island, he began exploring. During the first full week after getting settled, he ate lunch and dinner at a different downtown restaurant each day. That’s fourteen different places, fourteen meals, fourteen experiences. Blistov knew that food was a good indicator of culture. He thought the food in Moscow was terrible, because it was strictly indigenous. He thought the food in Saint Petersburg was far better because it had been influenced by western European tastes for a hundred years, and so was cosmopolitan. St. Petes didn’t always have the raw ingredients to make art, but when they did, they made great art. He had eaten very well in his hometown. When the French nouveau cuisine movement came into vogue, he thought it was crap, because he liked the heavy sauces and the twenty hours stews that were the basis of traditional French cooking.

Anyway, he enjoyed what he ate in Charleston’s restaurants, except of course what the menus lauded as “real southern cooking.” Boiling a vegetable in water for three hours, throwing out the water that contained all the flavor, then adding a pound of butter and serving this mess on an inch thick clay plate was not his idea of good food. He also explored the shops of the historic district, and again was pleased by all the antiques he saw. Some of them were as nice as those in the Hermitage. Not as old, but still classy.

Blistov enjoyed this time, getting to know his new home. When February came and he found himself walking on the sunny beach in front of his house, he decided he had died and gone to heaven. During this winter he realized his money was dwindling, and soon he would have to get back to work. This was ok because basically he liked his work. Doctors like doctoring, lawyers like lawyering, and criminals like crime. He also recognized he was getting on in years a bit, and decided to give up the rough stuff in favor of gentile swindling. That is how he ran into Roger, and where the conflict between them began.

Blistov decided to fake an antique and sell it to a shop on King St. This is a time-honored tradition around the world; one third of the antiques in museums are fakes, and half of the antiques in shops are fakes. We won’t even talk about what’s offered on eBay. Blistov contacted some friends in Russia who contacted some friends in Amsterdam who contacted some friends in Boston who contacted some friends in the furniture-producing district of western North Carolina. Blistov spend a month up there, and when he returned to Charleston, he was in possession of a circa 1737 Heppleworth end table. And it was good. He had no trouble selling it to a shop on King St. for a $27,000 profit, which would pay the rent on his beach house for some time to come.

The conflict with Roger came into being when the antique shop sold the table to a local granddame for $37,000. The granddame was Roger’s auntie. The old lady had an English relative in the antique business, who, while visiting, told her it was a fake. The old lady took it back to the shop, which was one of the newer dealers on the block, and who said to her, “Madame, caveat emptor.” With the expression of that very non-Charlestonian attitude, the lady went to her lawyer, who sadly concurred with the antiques dealer: “My dear, you are out of luck.” But the old lady was stubborn and of great moral fiber, and didn’t just roll over. She went to her nephew, Roger, who she knew was involved in some sort of detective thing when he and his wife were not traveling in Europe. She explained her dilemma, and asked for help. She really didn’t like getting swindled. Roger thought, “Auntie, caveat emptor, and by the way you are rich so don’t sweat the small stuff.” Of course he didn’t say this, because he loved his auntie, and he did not particularly like that someone swindled her, either. That evening he told Gwen he had a new case.

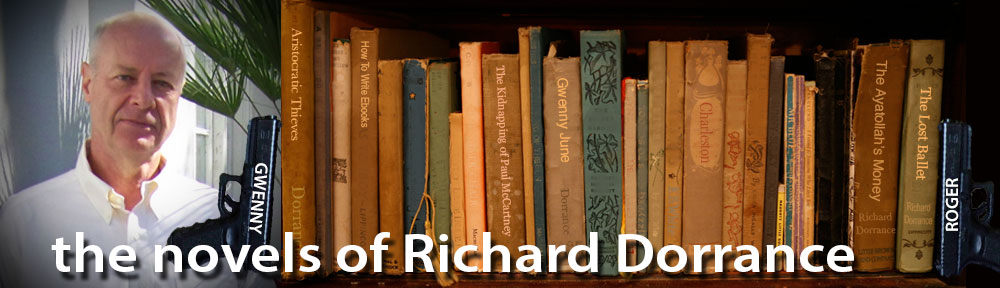

So you can see how the conflict between Roger and Little Jinny came to be. Roger was good at many things: choosing great wine to drink, loving his wife in and out of bed, shooting handguns, writing the occasional piece of romance fiction, and detecting. He did the detecting mostly for amusement, but sometimes for high fees, and occasionally because he felt sorry for someone. Like his Auntie.

His auntie, who wouldn’t tolerate a fake in her home, even a beautifully made one, gave the table to Roger. He rather liked the way it looked at the end of his third floor hallway. It didn’t take him long to backtrack the fabrication of the fake. His friends in the trade looked at it and told him it was made either in a workshop in south Philadelphia, or was made in a small factory in Brevard, North Carolina. Roger didn’t think much of the City of Brotherly Love ever since they demolished historic Connie Mack baseball stadium, which had the deepest center field in all of baseball, at 450 feet. No one could hit it out of Connie Mack to straightaway center, and Roger respected that.

So he headed for Brevard, found the furniture factory, made some discreet inquiries, and got the name of a craftsman who lived way out in the country. Using a persuasive combination of money and gun, he convinced the craftsman to tell him who he made the table for. Unfortunately all the craftsman really knew was that the guy was short and strong and scary, and had an accent. That was enough for Roger, who is very good at detecting.

One sunny spring day at nine in the morning, Roger climbed over the railing of the ground floor deck of Blistov’s beach house, pulled aside the sliding patio door, and entered Blistov’s living room. Blistov was sitting right there on the sofa, reading a Tolstoy short story. Roger pulled his gun, racked the slide, pointed it at Blistov, and said: “You swindled my auntie. Time to pay.”

Blistov didn’t even blink, but slowly lowered the book to the coffee table, remembering to dog-ear the page so he could find his place later. It was then that the conflict between the two men commenced. Both were smart, and cultured, and tough-minded, and results-oriented. The conflict that day ended with Roger winning, sort of. He told Blistov he had two choices: give him $37,000 in cash right then and there, or go to jail. Blistov took the jail option, and went there for six months. He decided he could do six months in a pansy American jail standing on his head. And he did. When he got out, he felt fine. He wanted something other than the southern-style prison food, but basically he was good to go.

And here he was, four months later, standing at a restaurant table, looking at Roger and someone he took to be Roger’s wife. A real relationship begins.